October 31, 2022

Peripheral Visions: Halloween Horror Double Feature

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 36 MIN.

Peripheral Visions: They coalesce in the soft blur of darkest shadows and take shape in the corner of your eye. But you won't see them coming... until it's too late.

Asking Price

Boris had traveled hundreds of light years. His journey had taken decades, even though he had booked passage on ships with lepton drives, exhausting his wealth in the process.

By the time Boris reached the planet Arinare in the Tantagilles system, he had only a few million ducreds to his name. He used most of that making bribes needed to gain access. But his research has been thorough; he knew exactly whom he needed to speak with, and who to pay, to make it happen. He also knew the argument he would make the one man who could grant his request.

Now that man entered the reception hall, a great room with walls of stone and high ceilings made from wooden beams and plaster. Tall windows towered on either side as Boris waited, the light of a white sun streaming in through the window. The atmosphere of Arinare had been terraformed and now ozone protected the planet's surface from the star's UV light. A network of satellites generated an EM shield powerful enough to deflect cosmic rays and large enough to provide a cloak of safety for the entire world.

The stairs were punctuated by several landings. The man stood on one located well above Boris, his back to the tall window that towered over the stairs. He was hard to see; he was washed out in the light, almost a silhouette against the brightness of the window. Even so, Boris felt that his thoughts... indeed, his heart... were being read through, assessed, and judged. He refused to entertain doubt: He knew deep in himself that he was worthy.

"I am Vasily," the man said. "I am the one you came to see."

"I thank you for this audience," Boris answered.

"What request do you have of me?"

"I wish to become an Archivist, like yourself."

"Many would wish that, with no idea of the work involved," Vasily told him – a response Boris expected and was prepared to hear. "Many assume that to be an Archivist is to possess wealth and power. But that is not necessarily true. There is a certain cultural significance associated with being an Archivist; we embed ourselves in every colony mission and accompany humanity as it presses ever outward into the galaxy, serving as living memories of culture and providing continuity with humanity's roots. But the task is not well-paid. I am fortunate to have personal resources rooted in pharmacological and technological innovations I pioneered on Earth. My industrial assets provide me limitless funds. That's why you find me in this magnificent home, appointed with a state-of-the-art multiformat library. Such resources are not available to all Archivists and the planets they serve. Most libraries, in fact, or pitiable by comparison to the one I have established here."

"And when you move on with the next colony mission you will appoint a junior Archivist to oversee this library, which you will have generously endowed," Boris said. "I know of your unique resources and your commitment to preserving human history and original Terrestrial culture."

That had been Boris' intended prelude to his argument, but Vasily had more to say. "It is true that many Archivists, even the ones who have chosen to live austerely, were once wealthy and powerful – enough that they became Archivists in the first place," the tall, forbidding man told him, his figure stark and still, an almost supernatural figure against the white light of the alien sun. "But fortunes change over time, as do priorities. Even one's perspective changes as decades, and then centuries, pass, and as one leaves one colony world for another and then another, always on the move, always carving out a new niche on the next frontier. Even the social status of the Archivists varies from place to place, waxes and wanes over time... we are not welcome everywhere. Radical separatists, utopians, and others do not welcome repositories of human culture, living or otherwise. They prefer to start anew. So, you see, becoming an Archivist is hardly a shortcut to fortune and glory."

"I do know that," Boris answered. "And I also know that over time the numbers of Archivists have dwindled. Some have died in spacefaring accidents; some have perished in colonies that fell into chaos and civil war; some have simply walked away from the work, vanishing into the galaxy at large. But you do welcome new Archivists into your ranks from time to time, with junior Archivists entering the vocation under the guidance and protection of established Archivists who act as their sponsors."

"What about the life of an Archivist attracts you?" Vasily asked. "The constant movement? The frequent periods of isolation? The task of preserving ancient, Earthbound history, as well as documenting colonial history as it happens around you?"

"All of that," Boris said. "But more to the point, I seek the thing that makes it possible for Archivists to be Archivists... to be a living memory of ancient days."

"Ah. I see. You seek immortality."

"Not as such," Boris said quickly, knowing that he had to make his argument compelling and very clear at this point. "There are many who wish to attain the gift of long life, yes, but I know that 'immortality' is an exaggeration. The universe itself is not immortal. Life in the universe is a transient phenomenon... playing out over scales of time unimaginable to us, but still, by the standards of cosmic time, a fleeting epoch. No, I'm not seeking prolonged life because I have delusions of eternal existence. But I do have a need for prolonged life. Not a selfish need, I should add. But neither am I financially equipped to purchase the means to prolonged life as the luxurious do, or the corrupt. In my case, both the need for prolonged life and the means to access it stem from a matter of professional necessity."

"Which is your clumsy way of saying you hope I will simply give you prolonged life," Vasily said. "But be sure to understand that even if you're not paying in money, the price for prolonged life can still be high. What do you have to offer?"

"The very life you make possible, spent in service to a work that has never been undertaken before," Boris said. "A work that only a man of exceeding discernment could appreciate."

"What work?" Vlad asked him, his dark, rigid form unwavering. He seemed more like a statue than a man – and more like some ancient weapon, a spear or a battering ram, than a statute.

"I am a historian," Boris said. "Before I embarked on this journey, eighteen years ago, I was still young. Despite that youth, I had authored definitive historical studies of several great civilizations – worlds that have now perished. The Folkauna of Temerity. The Millennellials of Wodala. The Justice Keepers of Koennyu. My work was regarded as foundational, revolutionary. I was offered appointments, showered with awards."

"Those hallmarks of accomplishment did not satisfy you?"

"I am a historian. Acknowledgement of my work gratified my pride, but not my professional ambition. I was given wealth, but I certainly know that wealth is fleeting, much as life itself, and my work means more to me than any amount of money."

"What is your ambition? What do you hope to achieve, and how is becoming an Archivist... with the prolonged life that entails... an end to that?"

"It is simple," Boris said, refusing to allow trepidation to enter his voice or his body language. He stood tall, kept his head tilted upward to look Vasily. The glare of the sun made it hard, but he hoped he was looking Vasily directly in the eyes. "The Archivists offer life that does not simply end after a handful of decades. You yourself made that possible. Long ago, on Earth, before the diaspora into the galaxy, you created the sangumites – the microscopic medical machines that repair cells, arrest the aging process, repair and enhance the brain's neurological functions, grant immunity from disease, enhance healing, even synthesize nutrients in times of famishment."

"Your research is thorough and impressive," Vasily allowed. "And you certainly know the means to prolonged life is my first and most profitable industry. Any Archivist can provide the means... but I am the original source. You sought me out for that reason, I presume."

"Yes. Your clinics provide the only reliable procedures. I cannot tolerate the risk of being given inferior sangumites, or being subjected to the procedure with any less than perfect competence. My work requires several centuries to be accomplished. Dying of rejection syndrome, or falling victim to progeria thanks to second-rate work would defeat my purpose."

"You still have not explained why you need so much time," Vasily said.

"Simply in order to travel the galaxy, examine its great and emergent civilizations, and make close note of how those civilizations ripen and then degrade and fail."

"Do you not understand this already?"

Another response he had anticipated. "History is the document," Boris said. "I wish to understand the process. By understanding the forces that drive humanity into the same patterns of ambition, then stagnation, then self-destruction, I hope to identify critical errors that can be corrected, safeguards that can be implemented, and perhaps one day avenues to true racial transcendence. Humanity can flower at last, equal to the great task of occupying the galaxy and not simply spreading among the stars like sparks from a bonfire – sparks that fly, settle, flare, and then disappear. Think of the light humanity could bring to the cosmos, if only we were better than we have been."

"The mechanics of human institutions are diseased," Vasily said. "And you seek a cure."

"I would not presume to cast the situation in a medical analogy," Boris said.

"No; that is my tendency," Vasily acknowledged. "The habits of an old biochemist. A very old biochemist."

"I prefer to see the great forces that act of humanity as a kind of mathematical equation," Boris said. "I hope to refine that equation – introduce new variables that can open the way to greater innovations, more substantial progress."

"And you suppose you can grasp the mechanics of such a thing?" Vasily asked.

"With centuries of continuity, yes," Boris said. "Generations of historians have offered their own interpretations, their own theories, but their knowledge is fragmentary, limited by human lifespans. To comprehend the lifespans of civilizations, we need a historian who will live as long as a civilization."

"And if the flaws in historical forces are actually flaws in the species?"

"Then perhaps someday there will be a historian who has lived a life that equals the life cycle of a species, and not just that of an individual. With that much time, we might hope for a perspective that surpasses what individuals were once limited to... limited perceptions, constrained comprehension, an inadequate willingness to see, absorb, and understand."

"A worthy goal for academic purposes," Vasily said, sounding reflective.

"And commercial purposes also," Boris said, trying to keep a note of desperate persuasion out of his voice. This, he was convinced, would be the critical point. Vasily was a businessman, after all. "To master the forces of history would be to create stability. I know you have relocated many times since you left Earth six centuries ago. I know you have established industries all during that time, and while some continue to thrive, others have been confiscated or demolished as governments descended into chaos and larcenous autocrats came to power. But what if your business ventures, and your financial resources, were guaranteed security to grow unencumbered by such setbacks? Imagine a limitless time horizon for your diverse holdings and industries to mature and expand!"

"An intriguing premise," Vasily said. "Flawed, I think... but that's just my opinion. The only way to test an opinion, or a theory for that matter, is to put it to the test."

"Then you will grant me my request?"

"It is an expensive procedure," Vasily said, his tone of voice still thoughtful. "The mites must be tailored to each recipient. It's a complex process, involving many technical specialists, much computer run time, resources from my lab facilities. From the look of you, whatever finances you once had have now been depleted. I suspect you spent everything you had in getting here."

"Yes," Boris said. "That's true."

"And it also testifies to the degree of faith you have in your theorem, and your confidence in your ability to accomplish your goal. That, more than any promise of profit, attracts me." Even though he could not see Vasily's face or his eyes, Boris felt the man's gaze rake over him with a cold calculation that provoked a physical chill in his bones. "You've offered the fruits of you work to me, but be honest: Those fruits are your reward. What price do you intend to offer me?"

Boris sighed and raised his arms in a gesture of surrender. "I am here as a supplicant," he said. "You hold the means. I only offer a possibility for how to apply those means. The asking price is yours to set."

Boris had researched more than the history of the Archivists and the trail of identities and locales that Vasily had traced across known space. He had researched Vasily himself, to the meager extent that it was possible. What little he had found on the man had painted a rough and incomplete picture of someone who liked power, and who liked to be praised.

If there was any truth to that portrait of the man, Boris knew that humility was his down payment on whatever price Vasily demanded.

"I agree to your request," Vasily said, and Boris heard a note of satisfaction in his voice. Boris realized at that moment he had been holding his breath. He tried to relax into the moment. "But only if you agree in turn to my requirements."

"Certainly," Boris said. There was little he would be unwilling to do or to surrender for the gift of so much time.

"Centuries from now you will come to a moment when you feel you cannot continue," Vasily said. "Whether you have your answers or not, I guarantee you that moment will come. When it does, you must find me, arrange an audience with me – much as you have today – and then surrender your life to me. That will be the payment."

"I..." Boris shook his head, not understanding. "I don't understand. To debrief me? To enslave me?"

"To kill you," Vasily stated. "As you will want me to. The mites will extend your life and make you hard to kill, but it is possible to commit suicide despite such enhancement. No matter how strong the urge to die, you must come to me. You must surrender your life to me, and me alone – and not take it yourself, or allow others to take it."

Another chill – this one a dark shudder, a presentiment of evil – passed through Boris, along with a fearful thought: What kind of sadist am I dealing with?

"Not a drawn-out death?" he asked, cautiously. "Not a death involving torture or debasement?"

Vasily laughed. "Certainly not," he said. "Rather, a death that acknowledges what I tell you here: That the gift of life I bestow on you is mine to reclaim. And also, that I know even now, before you even begin your great work, that it will come to nothing."

"You want the chance to... to say you told me so?"

"I want the chance to see my theory verified, much as you wish to see your own work to come to fruition," Vasily said. "And I wish the chance to offer another gift: The revocation of the boon you've requested."

Boris truly didn't understand what Vasily was asking for, or why, but he shrugged and then nodded. Anything could happen between now and that theoretical day, centuries in the future. His work would necessarily take him to dangerous places. Space travel itself was fraught with hazards. He might not survive to complete his work. He might never need to seek out Vasily for the gruesome consummation of his bargain.

But what, really, was Vasily asking for, anyway? Only his life, which Boris had always been ready to surrender in the pursuit of his dream.

"I agree," Boris said.

***

The process of providing him the mites was, as Vasily had said it would be, complex. It took months to prepare the tailored mites, which were specialized to his unique physiology and genetic structure. Once the mites were ready, the infusion itself was painful, the agony intense but brief; within moments the pain was gone and Boris' strength was returning, growing, his sense of well-being soaring, his senses opening up in ways he'd never experienced. The world came flooding into his mind, which itself felt renewed.

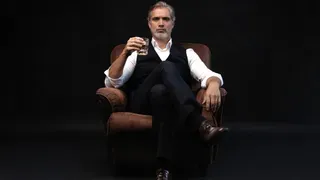

"The mites don't simply rejuvenate you physically," Vasily said, watching from the side of the room as the technicians completed the procedure. "They sharpen your mind." More visible now than at their first meeting, he was still inscrutable: Tall, shrouded in a black cloak. Even his eyes, now visible, were just as Boris would have expected: a piercing blue, cold and steady.

"Oh," Boris gasped – with awe, with excitement, rather than with pain.

"Yes," Vasily said, and for the first time a smile stretched his lips over his ageless, pale face. His luminous eyes rested on Boris a moment longer, and Boris looked back with gratitude.

"Thank you," Boris said.

"Just be sure you keep up your part of the bargain," Vasily told him, before turning and leaving the room.

***

More than eight centuries passed before the two shared a room again. When the day came – thirty years after Boris arrived at a point in his work, a point in his own long history when he determined he did not, could not, would not ever, understand the historical forces he sought to decipher – Boris no longer cared what sinister means of execution Vasily might have in mind for him. He simply wanted an escape from the crushing certainties and recurrent patterns in how human beings conducted themselves across time. He wanted to look away from the spectacle of greed and genocide that marred humanity's racial existence. He wanted his long, long life to end.

Vasily was now Vlad. He had changed his name every eighty-four years or so, as he had done ever since he had first left Earth in the first wave of space colonization over 1,400 years ago. He had relocated across a number of planetary systems, always on the frontier of human habitation as the species pressed outwards into the galaxy. He was now on a planet called Liang Qian Sibai – known more simply as Sibai.

"I congratulate you," Vlad said, standing in a room very much like the reception hall where they had first met 858 years earlier.

Back then, Boris' spine had been straight, his shoulders square. He had been possessed of a great certainty. Now he stood slumped, tired... defeated. Everything but old. Old, he was not. He was, biologically speaking, younger than when he had first met Vlad.

"Are you here to pay your debt?" Vlad asked, his voice echoing in the stone chamber.

Boris looked up wearily, his eyes sad and full of despair. "I'm here to die," he said.

"It's been a very long time, my old friend," Vlad told him. "Please, remind me. What was it you were looking for? And tell me – did you find it?"

Boris sighed heavily. From deep in himself – from a reserve of strength he had jealously guarded, as if knowing he would one day need it in a final press toward ultimate liberation – he gathered force and voice and spirit.

"I came to you with a project. I wished to be an Archivist, like yourself... one of the ageless who preserve the past, bear witness to the present, and help shape the future with a sense of cultural continuity."

"So I recall," Vlad said. "But why?"

"I wished to watch the processes of history. To witness..."

"Witness what?"

Boris sighed, too weary for this recitation. Surely Vlad remembered the reasons Boris had given him so long ago. "The cycles of human endeavor," Boris said. "Long ages of submission, subjugation. Then, intermittent bursts – flickers lasting only a few hundred years – when there comes a thirst for freedom and knowledge. A thirst for self-sufficiency, agency that originates in a sense of humankind as its own savior, as its own source of morals... and ethics... and direction. And then..." Boris shuddered, the strength he had summoned already flagging. "And then a willful rush to delusion. A psychotic determination to cling to trivia... to nonsensical stories of evil shadows and mythic gods and unrealistic rewards. Utter madness. Utter, gibbering idiocy chosen with great zeal and forcefulness over reason and responsibility."

"Yes," Vlad intoned. "And so you've seen the rise and fall of..."

"Of hundreds of worlds, dozens of democracies," Boris affirmed. "I have seen them all fail. I have seen them accomplish so much – become so bright, so hopeful – and then seen that light suddenly go dark, with war and turmoil and savage blood thirst sweeping them away. Fire, ash, cries of betrayal and despair. Cries of disbelief after frenzies of credulity. All so needless..."

"And why?" Vlad pressed.

"Why?" Boris asked.

"That was your question," Vlad said severely. "What you set out to discover. The reason."

"I..." Boris bent his head. "I don't know."

"Do you not? Even now?"

Boris shook his head, wordless.

Vlad stepped forward, walking down a flight of steps. As before, there were three flights of steps elevating him from where Boris stood.

Vlad paused on the first landing. "You still use the same name," he observed.

"I do," Boris said.

"Despite all the years, all the ways in which you must have changed. I see that you are indeed quite a changed man from the young, excited, brave fellow who sought me out the first time."

"I have changed," Boris said.

"But not your name."

"No," Boris said.

"Do you see how you were always destined to fail? The universe does change, and does demand change," Vlad said. "You cannot see that a man, and a species, must change also. Yes, humanity will change... eventually... into something else. That is the answer."

"Yes, I do see that. And finally seeing it... broke me," Boris said. "I don't know what sickness makes people go through this same pattern of self-destruction, but I see that it's a pattern that lies deep in the nature of the human animal. To escape it, we must cease being human. To evolve, we must... go extinct in giving rise to some other, better species. But even then, I fear we will fail. I fear there will be no change, no new and better species... only extinction."

"And this troubles you?" Vlad stepped down the next flight of stairs as he asked the question. His feet were light, his movements fleet. There was none of the heaviness about him that dragged on Boris – a heaviness of disappointment, of time itself, time accumulated deep in the bones, deep in the soul.

"My hope has become despair," Boris said. "I have seen the most peaceable worlds collapse into vicious, bloodthirsty warfare. I have seen the most enlightened people embrace superstition, the most pious people hurl themselves with abandon into homicidal wickedness while proclaiming their holy righteousness. I have seen the most prosperous people slide into desperate poverty, and the most freedom-loving people chain themselves to brutal dictators. And so it is, I have come to see, with everything."

"Everything?"

"I don't know if even evolution can save us from this horrible cycle, this... this vacillation between generosity and psychosis, between an urge to blossom into gods and a drive to degenerate into devils. The universe is vast, but it has only two rooms... two rooms that any conscious being must dwell within," Boris said, his voice drained, hollow, and lifeless.

"I see someone has been eating the godfruit," Vlad said.

Godfruit. Even now Boris smiled. Yes, he had eaten godfruit. He had seen the transcendent visions it brought. How young he had still been, six hundred forty years before, when he'd first tasted it., when he had come away from the dreams it inspired feeling that he had touched the divine... But even divinity had limitations. What he had seen as limitless light he now visualized as a figure eight: An endless loop that turned back on itself again and again, maddening, torturing, without end... without blessed cessation...

Vlad was asking a question. "Two rooms, you say. And you have dwelt in each of those rooms? Hope and Despair? Meaning and Madness? Purpose and Surrender?"

"I found my way from one room to the next, and I found that everything twists into its opposite," Boris answered. "Yes, my hope has become despair. My excitement for life has become dread of time, of still more time."

"But wasn't time the gift you sought form me all those years ago?"

"You were right when you said I would arrive at a place of no longer wishing to see, to witness... to experience... this grotesque charade of human life," Boris said. "My life must now become death, or I will never be free of the same patterns, the recurrent patterns that course through the universe."

"So you returned to me, as I required."

"I am here to honor the bargain we made, to pay your asking price for the long life you granted me," Boris said. "I can no longer bear to watch the hideous mockery that humanity either has become, or always was. I must ask that you exact your price and take my life from me."

"With those words you have proven yourself," Vlad said. "And I will exact the price we agreed upon." He descended the final flight of steps. Now he stood at the same level as Boris, though still several meters away.

Boris hesitated. A final, faint spark seemed to animate him as he looked up. "How will you do it? How will you deactivate the mites that repair my cells and preserve my life against disease, against famishment, against time?"

"I will not deactivate them," Vlad said stepping forward, his lips stretching into a hideous, humorless smile that revealed sharp, feral fangs. "I will simply drain them from you as I drink every last drop of your blood."

Boris, startled, stepped back with a yelp of surprise and horror. "What!" he cried.

Vlad paused, and then his grin was back – still inhuman, still bestial, but with a cruel humor. "The mites were never what gave me long life," he said. "The blood sustains me! It was always so – and I, and those like me, created the mites only so that the natural limits on humanity would no longer apply. Now that any human being can become immortal, any dictator can extend his life long past its natural span, we are no longer monsters. We are simply another stripe of men. But humanity, in its capacity for destruction and wrath, revenge and rapine, cruelty and suffering... humanity remains as monstrous as it ever was."

"Why did you create the mites?" Boris asked. "Was it truly to free us from death? Or to expose us to the horror of immorality, weaken us, annihilate us?"

Vlad chuckled. There was almost a tenderness, almost a sympathy in the sound. "We gave you this gift of long life so that your kind would forget to hunt us, and we could live in peace. The asking price for that peace? Ordinary humanity has been liberated from the constraints of time to blossom into its fullest expression of murder and spite. And yes... the existential horror you've encountered, the hard limits on understanding and free will, the surpassing of old horizons of understanding only to find that the universe is much more vast than any being can ever bring into its comprehension... the mercilessness of it, the mundanity of it, the sterility of it, the ceaselessness of it... the inescapable nature of it... all of that is part of our gift as well. Most of you never see it, and yet that hopelessness, the finality of the hard limits of knowledge and existence... that's the very thing that drives your kind to self-destruction again and again. In a stupor, you rise up to embrace reason and hope; with growing unease you discover that the universe, in its expanse and its nature, and even its mathematical certainties, is foundationally unknowable, unapproachable, unappeasable. Its cruelty is part of your own nature. The primal beast leaps up within your human heart and devours you, time and time again!"

"How do you behold this and not go mad?" cried Boris.

Vlad, drew closer, grinning with his fangs. "We made our peace with the cosmos. It is what it is. So are we. We pursue no higher meaning. We simply drink – and live!" With that, Vlad closed the last meter between them, his arms seizing Boris with tremendous strength, his teeth sinking into Boris' flesh. Boris' final cry was less a shout than a gasp – and a final disheartened groan of surrender.

Then the only sound in the room was that of ravenous drinking...

Esmeralda

It took a while for Dustin to get to the point. As he worked his way toward the reason he'd invited Jason Darius to his quaint, outdated home in what had once been a suburb of Lexington, he boiled water, shook leaves from a bag into a strainer, spilled the leaves, made a show of sweeping them up, then steeped a pot of tea. He poured the last of a plastic bottle of milk into a small ceramic pitcher – "A genuine creamer!" he boasted proudly – and then rinsed the bottle, screwed its cap back on, and tossed the bottle into an open bin on the corner of the kitchen that brimmed with more plastic bottles, empty tins, and other recyclables.

A few moments later, as Dustin was pouring the tea, a sudden sharp sound made him jump. The spout of the teapot wavered away from the cup and tea spilled over the white tablecloth.

"Shit, shit, shit!" Dustin cried.

Jason sighed to himself, trying to be patient.

Dustin set the teapot down, grabbed a tea towel, and started blotting furiously at the tablecloth. "This is brand-fucking-new," he exclaimed.

"Judging from the way the tea has beaded up," Jason ventured, "it's not actually cloth, which means it's stain-resistant."

Dustin paused. "That's right," he said, then grinned. It was a fleeting expression, though; Dustin's eyes darted to the refrigerator, as they had done repeatedly. Jason wondered if he had human remains stowed away, keeping fresh. Or maybe it was a case of appliance possession? Something supernatural was bothering the kid, and it wasn't just his jitters that made it clear. No one requested a house call from Jason Darius unless there was something strange going on.

"Why are you so nervous?" Jason asked, thinking the question might jump-start a disclosure of why he was here.

"I... I thought that noise was..." The kid shrugged. "I dunno."

"It's simple," Jason told him. "You washed the bottle with warm water. It's cold in here." Far colder, he reflected, than most people could afford to keep their homes, energy prices being what they were and the autumn being a scorcher this year. "You sealed the bottle with the cap, and as the bottle cooled, the air inside contracted. The external air pressure caused the plastic to shrink – hence the noise. It's physics."

"Yeah? You explain everything with physics?" the kid demanded, suddenly looking angry.

"My first career was as a physicist," Jason told him. "Before I got into, you know, demonology and whatnot."

"Well, can your physics explain why my house is haunted?" the kid demanded.

***

If Jason thought that would lead right into a succinct explanation of the problem – the nature of the haunting, the frequency of any strange happenings – he was mistaken. Dustin first had to detail what amounted to an autobiography.

Dustin had grown up in the neighborhood, among an extended family of cousins, aunts, and uncles. His Uncle Taylor had lived in this very house, which Dustin had inherited two months earlier following Taylor's death.

"Did the ghost kill him?" Jason asked, more to watch the kid's look of horror than because ghosts typically killed people.

But even that didn't derail Dustin's account. The kid had graduated from DeVos High. That was followed by a stint as a college football player.

Jason was more than a little bored when Dustin finally said, "I didn't know when I moved in that the house had... another occupant." He was staring nervously over Jason's right shoulder as he spoke, looking at the refrigerator again.

Maybe it wasn't a possessed appliance. Maybe he was just hungry. It was about lunch time; Dustin was a big man, and looked like he could eat often, and plenty.

Jason was cradling his teacup between his fingers, drawing warmth through the thin blue ceramic. Again he thought about how much Dustin must pay to keep the house so cold. Large men overheated more easily than skinny guys like Jason, but even for someone built like the kid was – six and a half feet tall, shoulders wider than the refrigerator that had him so nervous – the place had to be uncomfortably chilly.

The house looked to be more than a century old, following the lines and ratios of early-to-mid-21st century architecture. It certainly was not a modern dwelling, with all the appurtenances that smart, sophisticated homes now offered. Even the fridge was well out of date.

Dustin, much like the house and its uninspired décor, emanated ordinariness. He seemed nice – which was, of course, simply a way of saying that he was inoffensive, and seemed a little dull. If anything, that spoke to the likelihood that something strange really was going on. The people who sought Jason's help were typically more given to spinning fantastical stories from mundane clues: Homeland Security agents, or Neo-Goth musicians, or people who dabbled in dark designs of conspiracy, necromancy, or so-called psychic research. Such people tended to dramatize whatever problems they were facing, and usually there was more of over-active imaginations than the occult about their worries. It was rare that Jason was drawn into any truly paranormal situation. His initial interest in this call had been that the kid had offered him his fee in BlocTic, which was Jason's preferred cryptocurrency.

Now, though, Jason was feeling some real interest, and he wished all the more fervently that Dustin would cut to the chase. Finally, Dustin took a deep breath, looked Jason in the eye, and said: "Ghosts don't bother me. I see them all the time. I wouldn't even care about the one in the house, except she's... different."

"Just so I understand," Jason said, leaning forward and setting the teacup down. "You see dead people?" He chuckled at his own joke.

"Huh?" Dustin frowned. "You making fun of me?"

"No. I believe you. I was just kidding... that's a line from a movie. A really old movie." Jason only knew this because of his friend Henry, the HomeSec guy who sometimes consulted him. Henry was an incurable cinema aficionado. Even now, with governmental controls coming into effect over what ordinary citizens were permitted to watch, Henry was bold in accessing, downloading, or even securing old movies on physical media and then playing them on his dilapidated, many-times-refurbished laser disc system.

"It is?" Dustin seemed genuinely surprised. "I don't know. I don't watch movies much."

"Well, I guess it's a pretty standard phrase," Jason murmured, more to himself than to Dustin. Henry insisted that it once had been the movie's tag line, and, more than that, some sort of culturally significant slogan.

"Really?" Dustin's eyes widened. "Do other people see them too?"

"Uh..." It took Jason a moment to understand that Dustin's mind had skipped back to his ghost problem. "Well... I have spoken to a few people in my time who say the same thing."

"How do they describe them?" Dustin asked. "The ghosts, I mean?"

"Let me ask you that same question," Jason suggested.

"But I don't know anyone else who sees them," Dustin said.

"No – what I mean is, why don't you describe them for me."

"Oh... so that you'll know whether I'm telling the truth," Dustin said.

"Yes. And so that I'll have an idea of whether what you're seeing is genuinely ghosts, or maybe something different."

"Like what?"

"Well, if you had a cortical implant, you might be one of the very few cases in which your implant enabled you to perceive parallel universes. Or it's also possible that you could be seeing..." Jason paused; it was always a delicate matter to bring up the subject of Celestials. "I don't know, exactly. Angels. Or devils."

"Hah!" Dustin guffawed. Then, seeing Jason wasn't joking, he said, "Sorry... but, um... I don't believe in any of that."

"But you do see ghosts."

"Well, no. I mean, maybe. But I never thought of them as ghosts, exactly. I mean, the way other people think about them. I thought it was more like... impressions. I think that sometimes people make impressions of themselves. Like the cosmos takes a photograph, and that image remains in that place for a long time. But it's just an image. There's no mind there. There's no living presence. So it's not really a ghost, it's just..." Dustin shrugged.

"An impression," Jason filled in.

"Yeah!" Dustin brightened. "You understand."

Jason didn't, actually, but he had long since discovered that repeating people's own words back to them made them feel heard and understood. "So," Jason said, "you see these impressions. What are they like?"

"They don't do anything, really. They just appear and stand there. Or sit there. They don't move; they don't interact. They just stare. Except for the ones whose eyes are closed. And there was this one guy who didn't even have any eyes. I think – "

"Okay," Jason said, trying to keep Dustin on track. "So, what is it you want from me? Verification that you're actually seeing something real? Are you afraid you might be mentally ill?"

"No," Dustin said. "I know they're real. I think I know what they are. They don't bother me. They're part of the landscape."

"So why am I here?" Jason asked.

"Because there's a ghost in my house," Dustin said. "I mean, like, a classic ghost."

"I thought you said that these... these 'impressions' are not really ghosts?"

"They're not," Dustin said, "and that's the problem. At first I thought she was just like any other impression of a dead person. I thought she was just an image preserved in time. She'd appear and disappear like other impressions: Randomly."

"So what's different about her?"

"Well, she appears a lot more often. I usually only see most impressions once or twice. Like, on my walk to work there's this one guy I've seen three or four times now. That's very unusual. But this woman in my house..." Dustin looked over Jason's shoulder once again. "I see her all the time."

Jason turned in his chair to look where the kid was staring. He didn't see anything.

"Is she there now?"

"Yes," Dustin said. "And I think she's listening to me tell you about her."

"So, she reacts to stimulus, unlike other apparitions you've seen."

"Reacts! Yes!" Dustin looked at Jason again and grinned. "That's exactly what she's doing. When I first saw her, she would just stand there, like the others do. But then she started looking at me. And then..." Dustin raised an index finger. "She started pointing at me. And I'd be, like, 'Do you want me to move out of your house?' I mean, it would be a hassle. I like having my own place. But I offered anyway... it just seemed the gentlemanly thing to do. But she wouldn't explain. She'd disappear."

"Is that normal?"

"Yes, totally. The impressions... what did you call them? The Appalachians?"

"Apparitions," Jason said.

"Well, the apparitions always just blink in and out. It's like something aligns, and there they are – just a for a moment or two, usually. Like a trick of the light, only the light comes from the past into the present."

"Like a photo."

"Like a holo, actually, because they have dimension. They just don't have any substance."

"So, she points at you," Jason said.

"Right. And then the other day she did something new. She turned and walked up the hall."

"Did she go someplace specific?"

"No. She vanished."

"Did she make a sign, or do anything odd? Did she turn back to look at you?"

"No," Dustin said, frowning, recollecting the moment. "She... she kind of turned, I guess. But then she just disappeared."

"What do you mean she 'kind of turned?' "

Dustin shrugged. "I don't know. I was across the room when she started walking up the hall and I was trying to catch up with her and see what she was doing. I couldn't see up the hall until the very last second. When I had her in sight again, that was a split second before she disappeared. And yes, I think she was turning, but she didn't turn to face me... oh!"

"What's up?" Jason asked, as Dustin's eyes darted over his shoulder once more.

"She's pointing again."

"Pointing at you?"

"No. Pointing at you!"

"Me?" Jason turned in his chair once more and started at the spot by the refrigerator. At that moment he felt a chill run down his spine: Because Dustin was spooking him? Because of an unconscious association with the fridge, with cold?

Or simply because it was so cold in Dustin's house?

Jason stopped to consider that for a moment. He'd assumed the kid had a central air unit and enough money to run it. But now he wondered if the chill in the house was due to the presence of an actual ghost. The literature had described this sort of thing, but Jason had shrugged it off. Like Dustin, he didn't believe in ghosts. Celestials, yes; he'd had firsthand experience with them. Astral projection, certainly – from talented, but living, people. But ghosts? The idea had never made sense to him.

Yet, here they were. The kid was describing apparitions in just the way others had described them to Jason, but he was also claiming that an apparition was interacting with him, showing signs of consciousness and volition.

Dustin was on his feet.

"Is she moving?" Jason asked.

"No," the kid told him. "She's still pointing at you."

"Why me?"

"How the hell do I know?" Dustin asked.

Jason thought. "Have you ever tried talking to her?"

"Yeah. Sure. All the time. I'm like, 'Hey, can you not, like, show up if I have a girl over?' And, 'You better not be spying on me when I'm in the shower. That's totally rude.' That kind of thing."

"Have you asked her what she wants?"

"Oh yeah, a bunch!"

"I mean, have you played twenty questions with her?"

Dustin looked at Jason with a perplexed frown. "I don't get it. What do you mean?"

Jason sighed. "Okay, let me try. Where is she?"

Dustin pointed to the refrigerator.

"Am I looking at her?" Jason asked, staring squarely at the appliance.

"No, she's off to the side a little. To the right. And she's taller than you think."

Jason adjusted. "Now?"

"Yeah, kinda. I think so," Dustin said.

Dustin saw nothing; not the slightest shimmer, not the slightest shadow. "Well, all right. I'm going to try talking to her myself. Okay?"

"Yeah, man, go for it."

Jason took a slow breath. What did one say to a ghost? "Uh, hello. My name is Jason Darius. I'm an expert in the occult. Do you know that you are no longer living? Do you know that you are a spirit?"

Jason kept staring at the same spot, seeing nothing. Dustin, standing near him, was breathing loudly – excited, rapt, maybe a little scared.

"Dustin?"

"Yeah?"

"Can you tell me if she's doing anything in response to my question?"

"Oh, right, you can't see her. Well, uh... she's giving you a dirty look."

"She is?"

"Yeah, kinda. I mean, she's looking impatient. And she's still pointing at you."

"Okay," Jason sighed. The ghost, evidently, was not impressed with his efforts. "Let's assume that you do know that you're... well, dead..." Jason paused, wondering if the ghost would take offense at this. Dustin was still breathing loudly, but not narrating whatever response the ghost might have had. "Dustin?"

"Huh? Oh – yeah. She's..." Dustin chuckled. "She's rolling her eyes at you."

Jason set aside an urge to roll his eyes in turn. Impatience never served him well when he was facing the unknown. "Ma'am," he said, "I'd like to help, but I don't know how. Do you mind if I ask you a few questions about the situation? For example, are you tied to this place because of some of traumatic or violent experience?"

"Oh," Dustin said. "I think that's a yes."

"What's she doing?"

"She looks really... angry. And sad. Oh, I feel so bad for her."

"Did someone do something to you? Or did you do something to someone else?" Jason asked.

"She's walking!" Dustin said suddenly.

"Where?"

"I think she's... yes, she's heading up the hall, just like last time."

The two of them moved the few steps to the right so as to see up the hallway, which led past a bathroom on the left and two bedrooms on the right before ending in a wall and a door that led into a third bedroom directly ahead. All the doors were closed except the bathroom; the hall had a dark, murky look.

Perfect for a ghost, Jason thought, thinking of how apparitions were depicted in Henry's beloved old movies.

"Okay," Dustin said.

"What?" Jason asked.

"She disappeared again." Dustin walked down the hall, past the bathroom. He paused across from the second door on the right, turning left and examining the wall across from the door. "She turned here, and she... she walked through the wall."

Jason looked up and down the hallway. "What's behind that wall?" he asked. "The bathroom? Is there a second entrance to the bathroom from that bedroom straight ahead?"

"No," Dustin said. "The bathroom isn't that big, and there's no second entrance. I guess I never thought about it, but... " He looked at Jason. "I bet there's a room hidden behind that wall."

Jason was thinking the same thing. He stepped forward and joined Dustin. Together they looked at the wall. It seemed blank, solid, ordinary. "Someone must have sealed up a room for some dark and horrible reason," Jason said.

"Why dark and horrible?"

"The literature about ghosts says they don't hang around this Earthly plane unless they want revenge, or... or..." He shrugged. "I don't know. But the answers are on the other side of that wall. You're gonna have to get a contractor or..."

Dustin snorted. "You kidding? Let's get in there right damn now." He walked back up the hall. "There's a sledgehammer in the garage," he said. "That'll do the trick."

***

It didn't take Dustin long to make a hole big enough for them to pass through. The room was there, all right; it was dark, and big enough for the weak light from the hall not to illuminate its far reaches.

Dustin reached over and felt along the wall with his hand. "Here we go," he said, flipping a switch. An overhead light flashed on, and the room lay before them, revealed.

A bed to the right, a form tucked into its blankets. A window on the far wall, admitting no light, covered over by the house's siding. A desk in front of that blocked-in window. Notebooks were piled on the desk, Jason saw, and a chair sat neatly nearby. In front of them, and slightly to the left, there was a chest of drawers.

Jason advanced into the room, his eyes fixed on the form in the bed. A mummified head rested on the pillows. He reached down and tentatively grasped the blanket. Pulling the blanket gently aside, he saw a similarly mummified arm – and saw, also, that a leather strap served as a restraint.

She had been strapped down to the bed and walled in, left to die.

"Holy mother fuck," Jason murmured.

"Did they... did they kill her?" Dustin asked, even his loud breathing now subdued.

"Who owned this house before your uncle?" Jason asked.

"His parents owned it before him. And I think my uncle's father inherited it from his parents. They bought the house new in, like, the 2020s or '30s." Dustin stared at the mummified form. "This must be her. My uncle's grandmother, I mean."

"Growing up, did you ever hear anything about her?"

"Not specifically. Not that I remember."

Jason crossed to the desk, picked up a notebook, and flipped through it, taking in paragraphs and then pages. He shook his head at what he read there. Then his eye fell on a stack of typed pages. He picked up the stack and leafed through it.

"This is poetry," Jason said. He picked up the notebook again. "And I guess this is her journal." He scanned a few more entries, flipped to the last page with writing, and read some more.

Dustin stood there, waiting patiently.

Jason glanced back at the form on the bed, then at the desk in front of him and the blocked-in window. He had read about cases like this – atrocities committed during The Madness of the late 2020s through the year 2064, when the Second Revolution had ended decades of theocratic dictatorship.

"Dustin, I think your great-grandmother was the victim of an honor killing."

"A what?"

"That's what they used to call it when the male members of a family murdered a female relative – a sister, a daughter." Jason looked at the form in the bed again. "A mother."

"What? Why?"

"Who knows? They had lots of reasons. Supposed crimes like... I don't know. Not dressing modestly enough. Having sex outside of marriage. Driving a car or traveling without a male chaperone. Having a job outside the home. Disagreeing with a husband. Or..." He lifted the notebook in his hand, then gestured with it to the typed pages. "This journal doesn't actually say anything like, 'They are tying me down and walling me in.' But she does write that her husband and sons were threatening her. Telling her to denounce her published work."

"Published?"

"It looks like your great-grandmother was a writer. And if this... this..." Crime scene was the term Jason wanted to use, but Dustin seemed far too freaked out for him to want to use words like that. "If this scenario played out in the 2030s, then, yes. That fits with what was happening back then. The government had turned from democracy to authoritarianism. Laws were passed that barred women from certain professions. Women were not legally prevented from publishing their work, but there were cultural prohibitions. And..." Jason gestured again with the notebook this time towards the bed. "There were cultural punishments for defying those prohibitions."

"But was it legal to kill people like this?"

"Not legal, no. But allowed. A man could claim patriarchal rights over his family, and..." Jason left the sentence unfinished. "Honor killings were all about defending the family's reputation. Which is to say, if others in the community were gossiping about a family because of a woman's actions, this was seen as a way for the family to regain respectability."

"So they murdered their own family because other people were making fun of them? That's so fucked up... But, I mean, here in America?" Dustin looked shocked. "In school they told us how this country was always, always a beacon of freedom and goodness."

"Yeah, well, don't believe everything they tell you. Especially not in school." Jason sighed. Not now that we're heading right down that same path to fascism all over again, he thought. "And it's not just that she published her work. It's what her work was about." Jason offered the sheaf to Dustin. "Look at the title."

Dustin took the sheaf and looked at the first page.

"Esmeralda? Was that her name?"

"No; if you look at the next page you'll see..."

"Oh, here it says the author is Glenda McCormick. Hey, she really is my great-grandmother. That's my last name."

Jason already knew this, but he said nothing.

"This is a collection of poems?" Dustin stared at the page, reading what was written there. "This dedication. 'To my wife.' I don't understand."

"We might find out the details from reading her notebooks, or the poems might explain it," Jason said. "But I don't think your great-grandmother was entirely satisfied in her marriage to her husband. I think she found... alternatives... that allowed her to have a more full and happy life. And I think she was brave enough to speak up about that, at least in these writings... which, by the look of this manuscript, she was preparing to publish."

Except they murdered her first, he thought grimly. And now her great-great-grandson lives here, and he can see ghosts. No wonder she's been trying to get his attention. She's angry at having been silenced.

Jason felt a warm hand on his arm and looked up. Dustin was gazing down at him. "What do we do now?" he asked.

"Now," Jason said, "we give your great-great-grandma her due. We give her justice. And we make sure she has that chance to speak – to say what she's wanted to say all these years."

***

Jason knew people... people with influence, that is; and he knew people who knew other people with influence. Usually, it would have taken a year or more for a book to be published, assuming anyone wanted to publish poetry. Jason's friends got it done in four months.

The sensational story didn't hurt. Glenda McCormick had been in a polyamorous relationship with Esmeralda Burke for almost thirty years when, in 2036, her husband, Chad McCormick, empowered by a slate of so-called "gender laws" and "faith laws," had ordered Glenda to break things off with Esmerelda, resign her university professorship, and cancel the contract with her publisher for her new book of essays.

Glenda had refused her husband's demands. Her book of essays had been published – and then suppressed. Glenda had pressed forward, preparing her collection of poetry for publication and keeping her wonderfully frank and articulate journal. The society she described (and the family life she endured) were hideous, but her writing was lovely.

Jason's friends didn't just publish Glenda's newly discovered work; they organized a PR campaign that put Dustin in the news feeds and made him the primary story on the major talkverts for weeks. The books were not just offered in standard electronic format; they were produced in special paper editions.

Esmerelda shook everything up, and Glenda's journals sparked a national conversation and emboldened women, and others, to push back against the tides of renewed oppression.

"Who knows?" Jason said to Dustin, as they two of them stood in the restored room. The house was slated to be converted into a museum; Dustin had moved to a modern apartment across town. "Maybe your grandmother's story will wake people up. Maybe we won't have to go through all of that again."

"I bet she'd like that," Dustin said, then sighed. "But I worry that my great-grandmother won't get any peace with people tromping through her house. Coming to see the very spot where..." He looked at the bed. The mummified remains had been removed. Dustin had bought a niche at an upscale mausoleum for their proper interment. The bed now had a neat, innocuous look, as opposed to the horror show it had been, hidden away in the dark, for a century.

Jason was staring at the bed, too. A woman with white hair was sitting there, smiling at him. She had an elegant look. She was even wearing clothes – spectral clothes that seemed made of light, that shifted and blurred and seemed to coruscate with brilliant colors. The woman waved, then got to her feet, walked toward the still-blocked over window, and vanished.

"I don't think that's going to be a problem," Jason told him. "Now that she's had her say, I think your great-grandmother is, long at last, at peace."

Next week our eyes will be shocked by a flash of light. What emerges then will be a world forever changed, and two men alone among the relics of a vanished civilization, until, one by one, a small group of children find safety and shelter with them. Josh and Darren will protect their newfound family against all things known and unknown. Their battle cry: "Here We Are!"

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.