April 25, 2022

Peripheral Visions: Tour Guide

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 33 MIN.

They coalesce in the shadows and take shape in the corner of your eye. Peripheral Visions: You won't see them coming... until it's too late.

Tourguide

The irony was that his was a story he could dine out on –�but Don didn't need to, since he had a generous budget to eat, drink, travel, and enjoy himself.

Josh wanted to hear it.

"Well," Don said, as he poured a refill of the expensive French white wine into Josh's glass, "I was doing social media stuff..."

"I know, I've seen your old videos on SmyTube and Image Bank," Josh said.

"That's still out there?" Don slid the cold, damp bottle back into the ice bucket that stood next to the table. The restaurant, a place called Devant un Précipice, was a small place, quaint, and, at this hour of the afternoon, quiet. The town itself – an elegant flyspeck in the South of France – seemed a larger reflection of the establishment: A few streets winding through a cluster of red-roofed buildings, nestled unobtrusively into the Provençal landscape.

"The MegaNet is forever," Josh commented drily. "And, I mean, you had content all over the place..."

Don looked over at Josh, smiling at the remark. "Yes, SmyTube and Image Bank, and also Widgex, and Flaytron, and Semipress. And, I don't know, it must have been half a dozen others."

"Did you actually make a living off all that?"

"Oh, sure! I mean, I was still living with my parents when I was an influencer on those platforms, so I didn't exactly need to make a living. But when I started getting big, I started monetizing. Pretty soon I was earning a living for the whole family. And then came the book deals, the TV stuff, the travel... my parents made managing me their full-time jobs. More than full time."

"But you weren't doing travel and lifestyle content back then," Josh said. "Weren't you more into, like, ecology and stuff like that?"

"Yep." Don smiled ruefully and picked at his fish. Its preparation was sublime, and its presentation exquisite. The blackboard on the wall, which listed the day's specials and prix fixe lunch, claimed that the fish was caught from a local stream, but Don was almost certain that was a lie. Transnational corporations had long since vanquished environmental regulations in every one of the world's nations. There were no more fish living wild in streams, and if there had been, Don certainly would never have dared eat them.

Not that the farmed fish were probably any less toxic, he reflected. Not since regulations regarding food production had been done away with. At least the wine was genuine; the vintage was almost thirty years old. It was an expensive bottle... very expensive... but that had been part of his contract: Seek out and savor the best.

Silence had descended as Don lost himself in his reflections. After a moment, Josh spoke up again: "So, how is it you're doing travel and leisure writing now?"

"Hm?" Don looked up. "Oh – I'm not actually writing anything. I just... do this."

"Do... what?"

"This." Don shrugged. "See places. Have adventures. Enjoy wonderful meals."

"You made that much money?" Josh asked, laughing a little as he spoke – a way of showing his shock, astonishment, and disbelief. "You retired at, like, age sixteen or something?"

Don was used to the response. He'd told the story so many times he had it down pat. "In fact," he said, "I kind of did make a lot. Well, not really, considering today's prices for even really basic stuff. But I did make a lot of money. A lot. It's just that I make more now. And I don't have to pay for any of this... the travel, the lodging, the fine dining, the clothes."

"Escorts?" Josh winked at him.

Don frowned for a moment.

"Sorry," Josh said. "I know that's kind of a rude word."

"No, it's okay," Don said. "I mean, if you're comfortable with it, so am I."

Josh shrugged and took a bite of his quail. "I mean, why hide behind euphemisms?"

"You'll have to tell me more of your story," Don said. "How a nice American boy ends up vending companionship in the South of France."

"Sure, but first," Josh said, "I think you were about to explain your own interesting job before I sidetracked you with questions about social media."

"Ah, right. Yes," Don said. "I was about to tell you about how I became an Experiencer."

"What is that?" Josh asked. "That's a job?"

"That's just what I call it," Don told him. "As far as I know, I'm the only one. But it's more than a job. It's a vocation. And it's a miracle. And it's... it's..." His voice caught. He spent a moment composing himself. Then he looked Josh straight in the eye with the expression of a desperate man, a doomed man.

"It's a deal with the devil," he said.

***

His parents had parked him in the corner of the hotel lobby. Don didn't like the hotel – it was too grand, too luxurious, exactly the sort of thing he railed against in his videos and social media posts. He'd become an impassioned and articulate voice among the emerging new wave of youthful eco-advocates; he'd even spoken at corporate shareholders' meetings. His parents believed the next step was to secure a speaking engagement with one or another branch of the U.S. government, though Don privately doubted that was ever going to happen – not with a super-majority of Theopublicans in both the House and the Senate, all of them loudly proclaiming him to be a "socialist" because of his ecological views.

Don was neither a socialist nor a communist. He was just a kid who wanted there to be a future, and a livable climate in which to live in that future. He'd done his research and he knew capitalism, with a few incentives from government, could be a solution to an array of problems: Everything from desertification to the global shortage of potable water to the ever-deepening energy crisis could have market-driven solutions. The government, however, seemed more focused on protecting the entrenched interests that were driving the planet toward a mass extinction that would, in all likelihood, eventually encompass the human race along with all the other species that were vanishing.

It's only suicide if you agree to it, Don thought darkly, staring at a fancy potted palm. Otherwise, it's murder. So much for the 'Culture of Life' the state religion is always harping on about.

"Donald Prentiss?" a man in an expensive looking suit and the dark sunglasses said.

Don looked up warily. He almost expected to see a journalist – one of those weaselly right-wing guys with a phone or a camera, looking to catch him out on video saying or doing something stupid, or even... as he was doing now... sitting in the lobby of a hotel whose opulence was a red flag of wastefulness and environmental recklessness.

But the man speaking to him wasn't a skinny, jumpy, yappy journalist. He looked more like one of President Kirsch's secret police... the not-so-secret operatives of a brutal cadre that had recently started snatching people off the streets in broad daylight, stuffing them into black SUVs while frightened bystanders looked on and did nothing.

But Don didn't get a sense that the man was going to try to snatch him. He was only fifteen, but he'd learned how to assess people. What he saw was cause for caution, but not alarm; the man was clearly a professional, and capable of doing some damage, but he wasn't some hired goon.

"Yeah?" Don asked.

"Mr. Prentiss, I work for someone who would like to talk with you about a business opportunity," the man said. "Do you have a moment?"

Don glanced around. If this was a legitimate business offer, one or the other of his parents should probably be there. If it was some sort of scam – or a threat – then both of them should be there, recording the encounter with their phones.

"He wants to see you alone, of that's all tright," the man said. "And it won't take very long."

Don didn't answer; his stare remained skeptical.

"It's on the level," the man said. "My employer really does have a business proposition."

Don hesitated a moment more. But he had an independent streak, and he was getting bored of being shepherded around, with Mom and Dad brokering deals on his behalf. He shrugged. "Okay," he said. "Lead the way."

The man gestured across the lobby to where an elderly man sat in a chair identical to the one in which Don slouched. The chair was one of a cluster arranged around a low, glass-topped table. The elderly man offered Don a smile.

"You all couldn't just come over and introduce yourselves?" Don asked the man in the suit.

The man didn't reply; he simply stood there, his hand still stretched out in the direction of the elderly gentleman.

Don sighed and got to his feet, then crossed the lobby. As he approached, the elderly man's smile grew wider. He indicated the chair closest to his own, and invited Don to sit.

Don dropped into the chair and looked at the elderly man.

"My name is Caduceus Trimble," the gent told him.

"Don," the teenager said, his skepticism not easing up.

"Yes, the bright young man who has made all those videos and all those speeches. Quite the leader, quite the spokesman for your generation."

Spokesman? Don knew what it meant, but the word sounded strange. Theopublican state lawmakers had been busy around the country making it illegal to use certain kinds of words – including gender-neutral terms such as "chairperson" and "spokesperson" – but the statespeak, as critics were calling the imposition of officially approved vocabulary, still landed wrong on Don's ears.

"I bet you'd call me that even if I were a woman," Don said.

The elderly gent looked momentarily puzzled. "They call you a new Greta Thunberg," he said. "If you were a girl, I'd wouldn't ignore your effectiveness. Is that what you mean?"

"No," Don said. "Never mind. Look, what can I do for you? Your rented muscle over there said something about a business opportunity."

"Yes." The elderly man gripped a walking stick, Don noticed for the first time; his hands were dry-looking, thin, corded. They twisted around the stick's handle in something like excitement. "I've made my fortune sponsoring innovative new technologies."

"And so... what? You want me to shill some new air-purifying technique, or some new plan to build desalination plants?"

"God, no," the elderly man chuckled. "The planet is well past the point where those things will do any good. Terraforming towers to restore the atmosphere? Genetically engineered sea life that will devour the garbage we've dumped into the oceans for the last century or so? So-called zero-point energy? None of that is going to solve the crises we're facing."

"Zero-point energy would solve a lot of problems," Don said.

"Except it won't. Because the people who make money on the old ways of producing energy won't let it. It's cheaper to let the world burn than it is to adapt clean energy... to preserve, or conserve, the world we live in."

"And yet, you all keep calling yourselves 'conservatives,' " Don grumbled.

The old gent's smile didn't waver. "We're not here to discuss such things," he said. "No, I don't have some new planet-saving technology to sell you on. And I don't want you to endorse anything. But what I do want is to offer you something that could actually make a difference someday."

"Oh yeah?" Don sat up, his face reddening slightly. "Like, I'm not doing anything to make a difference now?"

"Frankly, no." The elderly gent's blue eyes seemed to sparkle. "You're shouting. You're working people up, especially young people. A lot of older people, too. And you've most certainly caught my attention."

"So, do you want to help me? Or are you just looking to shut me up?" Don asked.

"I do want to help you, but not in the way you expect," the old man said. "I suppose you want money for your cause, or access to politicians... and I have those things. I have them in abundance. But they aren't going to do you any good. All the money in the world won't save the world – not at this point. And politicians are weak and cowardly schemers, up to and including President Kirsch. Especially President Kirsch, that grifting moron. He's using a tried and true formula... the recipe for authoritarianism. That doesn't make him smart. He's just following the repeating patterns of history, and he's doing it through by some brain-dead instinct I don't pretend to understand. But then again, so am I. And so, I'm afraid, are you."

Don frowned. His skepticism was turning to hostility.

"Don't misunderstand me, young man," the gent said. "It's not that I don't fully appreciate the justice of your cause. But people are people. You can chide and coax and argue, but they won't change their fundamental roles. And history is what it is – you can rage and accuse, but the patterns are always the same. Democracies rise, democracies crumble. A noble people reach for the stars, but then become distracted and disillusioned by manipulators acting from selfish motives. The great mass of a nation's populace simply want what they want: To survive, to thrive, to enrich themselves. Those who manipulate nations appeal to selfishness and pettiness, and the lowest common denominator invariably prevails... though always to the cost of the common man. Tricked into surrendering his wealth and his autonomy, the ordinary citizen becomes a foot soldier in a war against... well, against himself. And for what? A bounty, offered to the greedy by their oppressors?"

"Sure looks that way these days," Don muttered.

"Yes. Exactly. The only difference is that this time, when civilization crumbles and democratic government – government of the people for the people, rather than of the people for the rich – when democratic government goes extinct yet again, with science being supplanted by superstition and progress assassinated by calumny and childish vendettas... this time around, the great engines we've constructed to consume our natural resources in the swiftest, most efficient manner possible, those engines will continue grinding away, destroying everything that makes life on this planet possible."

"You're telling me all this?" Don scoffed. "I spend my life trying to get people to listen to exactly what you're saying."

"That's right," the elderly man said. "But it's a losing cause – that's the message I'm trying to get across to you. People living in a burning building can see the flames, but if they have decided to place their trust in a con man who tells them that there is no fire and no danger, then pointing out the obvious reality of the situation won't wake them up. They've chosen to burn, boy. Why don't you see that?"

Don sighed. "I do," he murmured. "I see it. But I can't... I can't just sit back and let it happen."

"You want to do something," the elderly gent said, nodding. "But that's different from having something to do. You're speaking out, and people hear you, but the people whose ears most need to be open to you are blocked off – by their own choice. Because what you have to say is too difficult, because nobody is going to pay them for listening to you, because you're asking people to give things up for the sake of the future, and they don't want to entertain the idea, even though what they have is being stripped from them a piece at a time anyway. In other words, your efforts aren't having any effect. Not where they need to. You see that, don't you?"

Don stared at his hands. His face was no longer red – it was white, pale with rage.

"Don't you?" the elderly man prodded.

"Yes, god damn it, I do," Don told him. "I see that. But that's your message to me? It's hopeless? People are so delusional that they'd rather burn in their sleep than wake up and save their home?"

"Yes." The elderly gent looked at Don steadily. "The people of today refuse to see what they're doing. They plunge the dagger into the heart of democracy all while denying they hold the dagger in their hand. They plunge the dagger into the heart of the planet, even as they insist there is no dagger. People prefer their delusions to reality. They prefer their delusions to the lives of their children, or even their own lives. They're selfish, spoiled, infantile, and entitled, unable to connect cause to effect, unable to own up to their own mistakes because then they might have to stop making those mistakes."

"So what do you suggest I should be doing instead?" Don asked angrily. "What my parents are doing? Trotting me around to sound the warning, hauling me around the country to try to reason with screaming crowds of people, people with ugly faces, ugly with hate, ugly with rage, screaming ugly things at me? Someone even took a shot at me in Georgia a month ago. A bullet went right past my ear. And did the cops do anything about it? They were cheering right along with the crowd, calling me a 'commie.' I don't know how I didn't get killed that day. And all my dad had to say..." Don swallowed hard. "All my dad had to say about it was now we could charge more for my speaking engagements. Oh, and it would drive more book sales. A book I didn't even write, although my name's on the cover."

The elderly man was looking at him with sympathy, and that made Don even angrier. Then his expression changed to something else – something cold and calculating. "Here's where my business proposition comes in," the old man said.

***

"Dessert?" the waiter asked them in French.

Don spoke in rapid, fluent French. The waiter nodded and walked away.

"Wow," Josh said. "I speak French well, but not like that. That was beautiful."

Don smiled. "I hope you like fresh berries, cream, and whatever else is in what I ordered us."

"I do when it's genuine," Josh said. "You think any of it will be?"

"This place has a reputation for real food," Don said. "That's what I'm paying for."

"Is your expense account part of this mysterious 'business proposition' the old guy offered you? Is this the story of how it is you... well, you do whatever it is you do?"

"It is," Don told him.

"What was the name of this guy again?"

"Trimble," Don told him. "Caduceus Trimble."

"Isn't he some sort of industrialist or something? Some big engineer or something? Like, did he invent the MegaNet?"

"He's a venture capitalist," Don said. "He's not an engineer, but he does have an eye for emerging and potential technologies that will pay off. He was an early investor in transphasic tech."

"What's that?" Josh asked.

"It's... well, it's special kinds of crystals that can vibrate at two different frequencies at the same time. It's a quantum physics thing. It's why we had the second informatics boom, the second big data revolution. It also helped ameliorate the energy crisis." Don sighed. "Though that was only a bandage on a missing limb."

Josh didn't pick up on his glum comment. "It's a new energy source?" he asked, sounding excited.

"No, but it's much more energy efficient," Don explained. "We run ten thousand quantum computers using the same energy that used to power one standard mainframe."

"Okay," Josh said, clearly not comprehending.

Don smiled. "The point is, he's super rich and he likes to usher in new technologies."

"So, was this trans-plastic technology the thing he wanted to tell you about?"

The waiter approached with a tray. Two plates with gorgeous looking desserts sat on the tray, as did two small coffee pots and two cups.

"The word is transphasic, but no," Don said. "He had a different innovation to sell me on..."

***

"Let me ask you this," Trimble said. "How would you describe the actions of the people in charge?"

"In charge – of government?"

"Ha! Hardly. I mean in charge of the world, not this puppet play they call a government," Trimble said.

"You mean the CEOs, the rich people, the... the..."

"The Owners," Trimble supplied.

"Right," Don said. "There's only one word for it: Criminal. "

"Quite correct," Trimble smiled.

A week had passed since their initial meeting. Don had grown so angry that Trimble had suggested they reconvene at a later time, but he hadn't let the initial meeting end before he without set the hook: There was no stopping the forces destroying the nation and the planet, he said, but he had a technological innovation that might help one day restore the world.

Despite his anger, Don had seen the value in that. He had agreed to the second meeting.

Trimble had suggested they meet in Trimble's apartment in New York City, and asked that Don bring his parents. "They will want to be there," he said. "Our next discussion will include some NDAs and other legal details. You're not at your majority yet, so you can't sign your own contracts."

Don suspected what Trimble really wanted was the chance to impress his parents with talk about money. He worried that Trimble's "new technology" would just be more of the same old rape and plunder – some new and improved way to take the tops off mountains in Appalachia, or some new deep-mining technique that would poison the ground water and carve ugly scars in the Earth, or some new kind of ocean fishing, though if the oceans still harbored life it was probably monstrous, or mutated, or both.

Still, Don's curiosity was piqued; more than that, what Trimble had said kept echoing through his head; the point Trimble had made about people choosing not to listen... not simply being lied to and misled, but actively participating in their own deception by embracing what they wanted to hear and ignoring unpleasant facts. The more he thought about that kernel of truth, the more Don believed Trimble had put his finger on the root problem.

People wanted what they wanted, and they didn't care who paid the price for it... even if it turned out to be themselves.

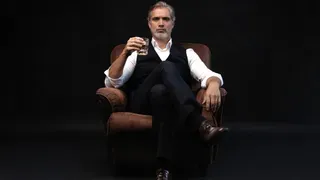

So here Don sat, in a pool of sunlight that slanted through a large south-facing window. The glass was tinted to take down the glare and filter out the UV rays that the ozone layer, thinning again after decades of recovery, no longer kept at bay. His parents sat together on a small sofa. Trimble held court from a large, comfortable looking chair – a wingback chair, all dark leather and luxurious buttons that created a quilted look across the back. Brass studs gleamed dully at the armrests.

Don's father, Pedro, was particularly excited. His mother, Danielle, held herself in check, but behind her reserve was a familiar sparkle of avarice.

"First off, what kind of money are we talking?" Pedro asked.

"No, I'm afraid the first thing is actually this: What's the nature of the work?" Trimble said.

"Yes, but the work must be worth some money," Pedro said. "How much?"

"Please, Peter" – Pedro had introduced himself as Peter, as he always did these days – "let's not get sidetracked," Trimble said. "The money is abundant, but it's a detail. Let's not allow it to become a distraction."

"I am responsible for my son," Pedro said, offended. "I need to know he's going to be treated right."

"Oh, he will be treated with great care. Very great care, indeed." Trimble hardly even looked at Pedro and Danielle; his gaze seemed forever fixed on Don in a way that seemed calculating and challenging by turns.

Don refused to allow himself to be intimidated. He returned Trimble's gaze. He thought he saw Trimble's lips curve in a slight, approving smile.

"The nature of the work," Trimble said, speaking over Pedro, who had started to say something more, "is that Don will travel the world. You like sports, don't you?"

The question surprised Don. "Uh, sure I do," he said. Did Trimble want him to speak with athletes? Or give speeches at.... what... soccer matches?

"Hiking, surfing, rock climbing? The media profiles all say that you enjoy those things," Trimble said.

"I do. When I have time for them." Don couldn't help the way his eyes slid, with a glimmer of resentment, toward Pedro, whose attention was fixed, hungrily, on the elderly gent.

"What about, say... skydiving? Hang-gliding? Skiing? Scuba diving?"

"I've never done any of those. Well, I've gone skiing, when snow was easier to get to, but not the other things."

"But would you be willing to try?"

Don shrugged. "Why not? They sound like fun."

"Yes!" Trimble shouted, startling even Pedro, whose rapt attention on Trimble had started to resemble a trance. "That's exactly what I want you to be doing. Having fun!"

Don shook his head, bewildered. "What?"

"Fun, boy. I want to pay you – and pay you well – for having fun." Trimble glanced at Pedro as he said this.

Danielle spoke up. "And this fun," she said. "Is any of it of a sexual nature?"

Don cringed inwardly – outwardly, too. He bit his tongue to stop himself from uttering a mortified cry of, "Mom!" That would make him sound too much like the embarrassed, shamed adolescent she'd just made him feel like.

"When he reaches legal age, yes," Trimble said, horrifying Don even more.

"With you?" Pedro asked. Don was shocked that his father didn't sound angry – if anything, he sounded mildly curious.

"My god, no. What do you take me for?"

"Sorry, sir, sorry," Pedro said, waving his hands and chuckling nervously.

But Danielle wasn't about to back down. "What I might take you for," she said, "is a perverse old man."

Trimble smiled at her. "And if I were? What then? Would you stand up and leave? Taking your precious boy with you?" Trimble glanced at Don and actually winked. He was clearly enjoying this, but Don couldn't fathom why.

Danielle looked like she wanted to say that was exactly what she would do. Instead, she stayed silent for a moment. Then she said, "What do mean, when he's of legal age?"

"What I mean is this," Trimble said, reaching into a discreet pocket on his white, comfortable looking shirt. He produced a small flash drive. "This is a contract," he said. "It specifies the terms of Don's employment – what he will do, how he will do it, for how long. And how much he'll get paid for it." He looked at Pedro again.

Don felt like he was being auctioned off. He tried to speak up.

"And how much is that?" Pedro asked, talking over Don.

"Hey!" Don hadn't meant to shout the word. It wasn't even the word he intended to say. But it worked; everyone looked at him, and no one spoke. Don forged ahead. "My parents might be fine with selling me as a sex toy – for the right price" – he shot a glare at Pedro. "But I don't think I'm interested in that, no matter how much money is on the table."

Pedro started to say something, but Trimble spoke over him again. "No, Don, you have the wrong idea. Your mother's question is crude, and misses the mark, but it's not irrelevant. Sex is part of life.. for most people, anyway. And it's part of a full and joyous life. But so is travel, and good food, and all the things that people enjoy."

"So... what are you saying, that you want to pay me for living my life?"

"Yes, that's it exactly," Trimble said.

Pedro and Danielle both tried to say something. Their voices tangled and canceled each other out. Don's eyes stayed locked on Trimble's.

"But," Trible said, "I want you to live an especially fun, full, and exciting life. A life that lets you see and enjoy the world's most beautiful places – before they are gone. A life that lets you avail yourself of the luxuries that middle-class Americans used to have within their reach: Air travel, cultural events. You've been protesting the world's slow, vicious murder at the hands of those who plunder it for riches; but I want to offer you a way to preserve some of the nature's bounty instead. I want your life to be a testament to the world's glories, before they are gone."

Pedro and Danielle were silent. Don wasn't sure what he should say, either, but he managed to stammer a question: "What the hell good will that do anyone?"

"Other than yourself, you mean?" Trimble smiled. "It will do a world of good. Literally – I mean it will do good for the entire world. The world of the future. A bleak, scorched, deprived world, full of desperate and resentful people who will wonder how their elders could have robbed them so completely, and done it with their eyes wide open, with so little regard for the future. You will provide them with experiences they won't otherwise be able to have."

"What? How?"

" 'How' is a matter of proprietary technology," Trimble said, his smile growing wider. "But, in general terms, it will be made possible by an interface between a recording device and your brain, with the implant processing and preserving information from all your senses."

"What do you mean, an implant?" Don asked.

"You want to record our son's experiences as he has them?" Danielle asked.

"Yes," Trible said, "an implant. And yes, I want to record your experiences. All your experiences. The implant will record every moment of every day. It will contain the sum total of your life. Then, later on... in the fullness of time ... your life experiences will be edited, archived... and here's the money part: Uploaded to the MegaNet, and marketed for streaming access on a subscription basis. You will be an encyclopedia, Don, of the world as it used to be, and all the marvels it had to offer."

"But... but why me?"

"You're passionate about preserving some of the world's beauty, aren't you?"

"Yes, but... its real beauty. Not some facsimile or... or home movie version of it."

"What we record will reflect the full sensory experience," Trimble said. "That's all anyone can take in of the world around them. No, we can't save the natural world itself. It's too late for that. But we can document what remains while it's still there."

"Last chance tourism," Danielle murmured.

Trimble look at her, delighted. "Yes, in a way. Absolutely."

"But fake," Don said. "Not saving the world, just... creating an illusion of it."

"No," Trimble said. "A memory. A recording, yes. But not enhanced, not falsified in any way... except in the editing. And who knows, perhaps some day we will sell the unedited recordings to allow people a fully immersive, all-occupying experience for days, weeks, even months or years, a retreat to times and places they could only visit through your eyes."

"But, I mean... why me?"

Trimble shrugged. "You're young. Your brain can adapt to the tech and use it to its full potential. And you appreciate, even love, the natural world. I believe that will give the recordings something special... and emotional aura. A joyousness. Simple sensory experience won't be enough. We need to capture a sense of gratitude and enjoyment that I think you have. I could organize some sort of national search, some sort of mass audition process... but that would mean publicity. I don't want to tip my hand, This is top-secret, proprietary technology, and in order to preserve my advantage that technology has to stay secret for decades to come."

"So I'd spend my life... enjoying my life," Don said.

"Yes. And you'd be underwritten with enough money to live to the fullest. Swim with dolphins. Climb Mount Everest. Hack your way through Brazilian rainforest with a machete, while there's still some rainforest to hack through."

"But what about love?"

"It's gonna be a porno movie every time he gets with a girl," Pedro said.

"Dad!" This time Don wasn't able to contain himself. "I told you. I'm not into girls. But still..." He looked at Trimble. "If I fall in love, that will be part of the recordings. My life with my... my husband."

"Oh, Donny, no!" Pedro said. "You know you can't. The court took that away. You know you can't, it's not legal anymore."

Don ignored him. "What if I don't want to share my private life?"

"That can't be helped," Trimble said. "Except that under your contract you won't have a... a husband. Or a wife. Or a life partner. You can have lots of lovers, of course... the more, the better. We all know the simple fact is that sex sells. But do you think the people of the future, the people looking to experience the better life that was once possible, will want to experience domestic drama? Quotidian family life?"

"Maybe," Danielle put in.

"No!" Don said.

"No," Trimble agreed. "Besides which..."

Don interrupted him: "I mean..."

"I know what you mean, Don, but that's not the content we're looking for," Trimble said.

"So you're not willing just to edit those things out?" Danielle asked. "Love, romance... marriage?" She looked at Don with a wistful smile.

"Editing isn't the problem," Trimble told her.

"It's time," Don said, with a sigh of resignation.

"Smart boy," Trimble nodded.

Don turned to his parents. "The world is collapsing too quickly. I'm going to have to travel continuously. Have adventures every day. It's not the sort of life that..." He fell silent, trying to comprehend just how completely the job would take over his life.

"It's not the sort of life that can accommodate a long-term partner," Trimble said. "Hookups, yes. Romance... for a few days, a week. But otherwise... " He shrugged. "It's still a big world, and you have a lot of ground to cover. A night of fun, a temporary partnership, those are to be expected for a healthy young man. But then you'll need to move on."

"Then I can't do it," Don said.

"No?" Trimble asked.

Pedro and Danielle stared at him from the couch, looking concerned. Worried, Don thought, about missing out on a biggest payday they'd ever see.

"Who would?" Don said. "We're not talking a job, we're talking about... about performing. Every minute of every day for... for how many years? Can you even tell me that?"

"I can tell you that," Trimble said, "based on the rate of the world's collapse, as well as the ideal age of the person making full-sense recordings using my new technology. But it's an answer that won't matter if you're not willing to do it."

"And why should I be willing?" Don asked.

"Well, young man, I can tell you that too..."

***

The night air was warm, of course – it was the South of France in March. Don and Josh had been walking off their meal for several hours. Don's narration had been punctuated by work: Taking self-guided tours through a church and a scenic cemetery, walking the quaint streets of the town. Wandering through a park. Sitting on a bench n the banks of a serene river that threaded between generous banks, the water now more like a trickle now than in times past.

"Tomorrow I visit a farm where they're growing sunflowers," Don said. "And then I tour one of the last operational vineyards."

"Why?" Josh asked. "It sounds boring."

Don opened his arms wide. "It's Provence! The world may slowly be baking, but the region still has a romantic sound for people. And it's not all about seeing the Grand Canyon or finding the best views on the island of Kauai'i. It's about the food, the wine... the fun." Don reached over and rubbed Josh on the back. "So, tonight we're gonna have fun. But you'll need to sign a release, because..."

"Because I'm going to be part of your sense record," Josh said.

"Yes."

"Our intimate time together will be digitized."

"Yes. And maybe replayed."

"By the people of the future. Because, what? They won't have sex years from now?"

Don shrugged. "Maybe not with healthy, attractive people like you. Or in a bed with soft, clean sheets, with a fragrant night breeze coming through an open window."

Josh shook his head. "I don't know. I didn't sign up for this."

"Not yet," Don said. "But once you sign the release, you're eligible for a bonus."

"How much of a bonus?"

"Generous," Don said, with a playful smile.

"That's not funny," Josh said.

"Aw, come on. It's a pun. Isn't 'generous' a – what do you call it – a term of art for people in your profession?"

Josh shook his head again, looking irritated... or maybe hurt.

"Look," Don said. "Let me put I this way. Are you a size queen? Because the bonus... it's big. Trimble has a fuck ton of money and he's not stingy, not when it comes to his pet project. It'll be worth your time."

"Well, in that case." Josh smiled.

"Yeah." Don smiled back.

"So," Josh said, "how does the story end? How did he close the deal?"

"Well, yes," Don said. "I was unwilling to devote my entire life... my entire life... to his recording project, even if it meant that people in the future could experience the world in a way that wasn't going to remain possible for much longer. But then he told me there was another reason..."

***

"Evidence?" Don said. "Of what?"

"That the world really is the way it is today," Pedro guessed. "You know how the state religion teaches that the way the world is right now is exactly how God made it? Like, the Theopublicans have passed laws that schoolteachers can be sued, writers can be jailed, museums can be shut down if they say that snow used to fall in December, bees used to do most of the pollinating for crops, people used to eat all kinds of fish right out of the ocean... tuna, cod..."

"Dad, that's dumb," Don said.

"No, that's right," Trimble said. "It is evidence. And that's exactly what I intend it to be. I want there to be a full record of the wonders we are losing, that the Owners are forcing us to lose. The theft, the vandalism, the murder – the abortion of the natural world, and the endless generations that will never live because of our greed. And I think you want this too, Don. I think that's the reason you'll do it. They can try to outlaw telling the truth, but if people can see it, hear it, feel it, taste it for themselves... the gift of a clement world, a world of plenty..."

"What?" Don scoffed. "There'll be a revolution? It will be too late by then."

"Not a revolution," Trimble corrected him. "Justice. Trials, Accountability. The Owners have made an art form and a political exercise out of gaslighting people. They won't be able to keep on doing it. Not with the sense recordings you'll be making."

"But why?" Don asked. "You're one of them. Why do you want the Owners to be held accountable?"

"Because I love nature, too... not just nature in leaf and cloud, Don, but nature in its array of scientific possibilities. But tyrants fear science, they fear facts. When tyrants have nothing real to offer, they resort to peddling dreams, illusions... fictions, fabrications, scare stories, and manufactured resentments. And also..." Trimble smiled. "I suspect in the future not even the Owners and their armies of paid brutes will be able to suppress the anger of the people and a demand for retribution. You'll show them exactly what was stolen from them. And you'll provide them with the evidence they need to prosecute their case against those they will hold to account. You will give a focus to their rage and help them articulate their desire for justice. Who knows? Maybe their fury will be restorative. Maybe your memories will give people a sense of something to strive for, an understanding of what they could hope someday to restore."

"Can I wait a few years?" Don said. "I mean, to live my life before it all gets recorded and then, eventually, shared?"

"No," Trimble said.

"Why not? The world's going to Hell fast, but not that fast."

"Actually, it is," Trimble said. "In just a few years, the last coral reefs will be gone. That's one example. But there's another reason. We can't, for ethical and legal reasons, perform an implant of this sort on someone under the age of sixteen. There's simply no such thing as consent for medical innovation below that age, even if your parents sign on. But we need a young brain, and we want to maximize the time we have available before the entire planet is a wasteland. The best solution is to implant the technology into the subject, whether it's you or someone else, as soon as they turn sixteen. And you're turning sixteen soon – in less than a month. So, you need to decide, and you need to decide now."

Don sat still, weighing the possibilities and the costs. His parents looked at him with fierce focus, as if they could will him into agreeing.

"So," Trimble said, leaning forward. "Will you do it?"

Don heard his parents holding their breath, felt the greed radiating off them.

But from deep inside himself he heard something else: A cry of rageful victory, a war-cry that resounded a conviction that someday, no matter how far in the future it came, there had to be an answer for the deliberate and malicious destruction of the whole world by a class of people with no empathy, no sense of higher purpose, and no capacity for remorse – not until they themselves faced whatever system of justice might survive in decades and centuries to come.

"Yes," Don said. "Yes, I'll do it."

Trimble's smile was the signature on the victory already written across his face. "Then let's discuss the finer details. Chief among them are the NDAs, which will have specific exceptions... people you will need to obtain releases from, but they in turn will sign NDAs of their own. But also, there's another stipulation you will find of interest..."

***

Their lovemaking had been measured, paced, artful. That was how Don had wanted it, and he was paying a lot for the privilege.

Don had been with a lot of men, and he had always been mindful of what he did with them. He'd made an art of giving and receiving sexual pleasure. It wasn't just a matter of gifting his experience to the future; he'd realized long ago that there was also a pleasure in itself in capturing erotic moments, more so than other fleeting moments in time. It was exhibitionistic, but it was also a matter of those things Trimble had said he wanted the sense recordings to convey: Gratitude. Joy. A deep resonance with the very substance of life, and the possibilities of living.

In a way, it felt like love, too – not love for a lifetime partner, but love all the same.

They lay resting in moonlight, Josh gathered into Don's arms.

"I thought you would want me to hold you," Josh said, "but here we are, the other way around."

"I like it this way," Don said.

"What about your audience in the future?"

Don chuckled. "They'll have plenty of experiences to choose from. But this is how I like it right now. And I'm not sure, but I think they're going to experience my emotions as they play these sense recordings back. That literally means if I'm happy, they'll be happy."

Josh laughed at that. After a moment he said, "So, how does the story end?"

"What do you mean? I told you. I signed up. I got the implant done on my sixteenth birthday and after about four months of integrating it into my brain's sensory processing system, I started on my career. Seeing the world. Meeting people, jumping off cliffs with a cord tied to my ankle, white water rafting, exploring ancient temples in Thailand. Spending two years in India, and a summer in New Orleans, and a winter at the South Pole..."

"Yeah, but Trimble said something about a codicil or something."

"Oh. Well, yes, I guess I did tell you that. I usually don't."

"You tell this story to everyone?"

"Not like I told you. Not in so much detail. But I do have to explain to my sexual partners..."

"Us escorts," Josh said drily.

"...why it is I'm having them sign releases and NDAs and everything. But I guess, I guess I wanted to tell the whole story once, tell it at last, because..." Don's voice trailed off.

Josh intuited what he wasn't saying. "This is your last trip, isn't it?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"I'm about to turn forty. They think the sense recordings won't be as good past that age. The theory is to use a young brain to adapt to the tech, but then stop before that brain gets old and risks spoiling all that work, all those memories."

"How would an older brain spoil recorded experiences>? I mean, they're already recorded."

"I don't know. Probably it wouldn't. But that was a worry, I guess. But apart from that, transphasic crystal memory matrices can store an amazing about of information... but Trimble seems to think that the implant's maximum storage potential is twenty-four years. So, that's the length of the contract."

"So your contract is about to expire. And then what?" Josh asked.

"They take it out. The implant, I mean. And then they download the sense memories, edit them maybe, create memory documents they can sell. I suppose they'll sell specific trips I've taken to different places, different kinds of experiences I've had. The food and wine memories. The South Pacific memories. Whatever. People will pay to see the world's beauty even as it's disappearing... the beauty that has already disappeared in the last quarter century. And maybe, like Trimble said... when people see what they've lost, what's been stolen from them..."

"What, revolt? Demand justice? I'm not so sure," Josh said. "Like, I know the Mid-Cents hogged the last of the good stuff in the world, and the Millennials before them, and the Boomers even before that, but I don't walk around every day thinking I want revenge. And anyway, revenge how? They're all dead."

"The greedy bastards who own the world and are trashing it are still here," Don said.

"Yeah? Well, good for them, I guess," Josh said. "I mean, that's just the way things are."

Don sighed. "How old are you, again?"

"Twenty-four," Josh said.

"The world is changing fast enough that you know what you're losing..."

"I have enough to worry about just getting through each day," Josh said. "I mean, I'm sorry if that disappoints you. We all can't be... what did that old guy say you were? Gretchen someone or other?"

Don chuckled sadly.

They were silent a while longer. Then Josh asked: "So, what happens to you?"

"What do you mean?"

"You know what I mean. They yank the implant, and – do you die? Do you end up a vegetable? Or do you not even notice?"

Don sighed. "They tried to tell me there was some hope I might survive. But I don';t se ehow. The implant itself is small, but it uses some kind of generative nonotechnolgy... it grew a whole web of tendrils that stretched into different parts of my brain. It's because of how denses are processed and memeories ar made... there's a network of very fine threads all throughout my brain. When they take the implant out, those tendrils will pretty much slice and dice my brain. Even if I did survive that, I'd be... I don;'t know, Mindless. Blind. I'd just as soon be dead and have it done with."

"That's harsh," Josh said.

"That's what I signe dup for," Don told him. "And, you know, I got what I paid for.

"You paid?"

"I mean, I'll deliver what Trimble has been paying m,e for. But I got something in return that... that no one else has probably ever had. A blank check to see, to do, to taste, to feel. The whoel world a la carte."

"But you said it was a deal with the devil," Josh said.

"It is. You know the old stories about people who sell their souls? For a lifetime, for some specific achievement – an Oscar, a Pulitzer, something like that. Or money. Or, in some stories, a measly seven years of high living. Well, I didn't sell my soul, but I did sell my lifetime, and to be honest, what I've experienced has enriched my soul. My bank account, too... if my parents were still alive they'd be inheriting millions. That's kind of a joke, I guess. All that money, and I don't have anyone to leave it to."

"Jesus," Josh said. "At least you feel like it was worth it."

"So worth it." Don paused briefly. "And in some sense, I guess, I'll keep on living through whoever plays my memories back in the future. Who else can say that? I guess I can't complain. I certainly ate well. And I met some..." He gave Josh a squeeze. "Some lovely people."

Josh turned in his arms, looked at him in the moonlight. "I'm sorry we have so little time," he said.

"Yeah."

"It might have been nice for you to have a chance to... to settle with someone."

Don laughed. "Don't get carried away. One day, one night."

"I just wish things could somehow be different."

"But I'm forty," Josh said. "And you're twenty-six."

Josh snuggled into Don's arms as though into a blanket. "Can't have everything," he said.

***

A burly man in an expensive looking suit held out the loader, and Trimble took it.

"Thanks," he said to the man. He didn't bother with a name – he didn't know any of their names, had never needed to remember them. They were all the same – suits, build, attitude. They did their jobs, and that was sufficient.

The first twelve-hour recording had been formatted onto the chip. Now the loader would transport the chip into the port installed into Trimble's skull, and the port would do the rest, sending impulses to the appropriate brain regions through nano-rigged cortical filaments. Timed and synchronized just right, those miniscule electrical impulses would become coruscating sensations overriding the dismal here and now, even overriding the blunted feel of life that characterized an old man's daily experience. If the tech worked right, Trimble wouldn't even need to spend any time learning to process the input; it would interface perfectly with his brain.

Trimble would be there, in the past, in a young, strong body: A body where the senses hadn't yet dulled, a body free of aches and pains, a body brimming with energy.

Running, Swimming. Dancing. Fucking. It was all here on this chip. A full twelve hours of time recaptured, vitality regained. More chips were being prepared – twenty-four years' worth of memories, twelve hours at a time.

Trimble could be young again, could live the life he had always wanted: Adventure, travel, fun. And all it had cost him were half a trillion dollars and forty-two years, a period of time split roughly in half between technological R&D and the decades spent to make real-time recordings.

He laughed, thinking about the line he'd fed the kid, Dom. Don. Whatever his name was. Justice for people of the future. Like everyone else in the world, the kid heard what he wanted, chose to believe the things he desired and ignore the rest.

Well, Trimble thought, it wasn't exactly a lie. It was justice of a sort, for what at the time had been a future version of himself. After all, Trimble thought, I'm an Owner. I run this fucking planet. I own these fucking people. It's the least of what I deserve.

Next week a terrifying vision comes into focus of a world powered by hatred –�and in need of a new source of energy. Will those who run the planet deliver fresh promise, or fall back on old horrors?

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.