Nov 10

“Bunny”: A Chaotic 24 Hours in the Life of a Queer Sex Worker on New York’s Margins

READ TIME: 3 MIN.

In his feature film “Bunny,” director Ben Jacobson takes audiences on a breathless journey through 24 hours in the life of Bunny, a queer sex worker whose birthday spirals into chaos and danger. Set in New York’s East Village—a neighborhood long associated with LGBTQ+ activism and bohemian culture—the movie unfolds against the backdrop of a city that is both sanctuary and threat for its most vulnerable residents .

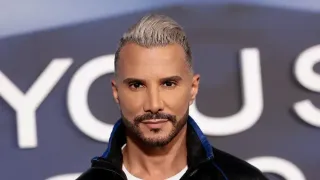

Bunny, played by Mo Stark, is introduced in the back of a police car, his clothes covered in blood. The story quickly jumps into action as Bunny escapes custody and sprints through the city streets, setting the tone for a day that will careen through violence, humor, and the bonds of chosen family. Upon returning to his apartment, Bunny is greeted by his wife, Bobbie , who presents him with an unconventional birthday gift: a threesome with another woman. The film’s ensemble cast soon expands to include the building’s landlord, an Asian-American woman with limited English; an Orthodox Jewish Airbnb guest with strict requirements; and Bunny’s father-in-law, who unwittingly gets high after consuming edibles .

As the narrative unfolds, it’s revealed that Bunny’s day has already been marred by trauma. While working earlier, Bunny was sexually assaulted by two men who hired him. The encounter escalates and, in the aftermath, Bunny is pursued by the men’s driver. A confrontation in Bunny’s building ends fatally when the driver falls to his death. Rather than focusing solely on the violence, the film underscores the solidarity and improvisational resilience of Bunny’s community: his best friend Dino helps him rally neighbors to discreetly remove the body and prevent legal repercussions .

Jacobson’s storytelling draws comparisons to filmmakers like Sean Baker and the Safdie brothers, known for their gritty, kinetic portraits of New York’s underbelly. The director’s use of handheld camerawork, erratic editing, and yellow-tinged lighting infuses the film with a sense of disorientation and lived anxiety, echoing the precariousness many LGBTQ+ people and sex workers face .

What distinguishes “Bunny” is its refusal to reduce its protagonist to victimhood. While the film does not shy away from the realities of sexual violence, accidental death, and drug use, its prevailing mood is one of dark humor and camaraderie. Bunny’s ethic of kindness—toward clients and friends alike—serves as a through-line, suggesting that sex work, for him, is not simply a means of survival but an expression of care in a world that can be indifferent or hostile .

The apartment building itself becomes a symbolic microcosm of the city’s diversity and the concept of chosen family, a central theme in LGBTQ+ culture where biological ties are often supplemented or replaced by supportive friendships and communal bonds. The building’s residents, with their clashing personalities and backgrounds, join forces in the face of crisis, emphasizing both the fragility and tenacity of these urban networks .

“Bunny” stands out for its representation of queer and marginalized lives without resorting to clichés or tragedy porn. The film’s lightness of touch—its “stoned silliness” and irreverent humor—offers a counter-narrative to mainstream portrayals of LGBTQ+ sex workers, who are often depicted solely as victims or criminals. Instead, Jacobson’s film is a love letter to a vanishing East Village, capturing both the gentrification that threatens these communities and the enduring spirit that persists in spite of it .

The film is scheduled for a limited theatrical release and video-on-demand premiere on November 14, marking a significant addition to the growing canon of LGBTQ+ cinema that centers queer resilience and the complexities of sex work .